What are biobank data?

Imagine a big library, but instead of books, this library stores tiny samples of people’s biological material (like a drop of blood or a small piece of tissue). Along with each sample, there’s information about the person it came from, such as their age, health conditions, lifestyle, and medical history. This “library” is called a biobank. These stored samples and data can be used to study diseases, discover new treatments, and understand how different factors (like genetics or environment) affect health.

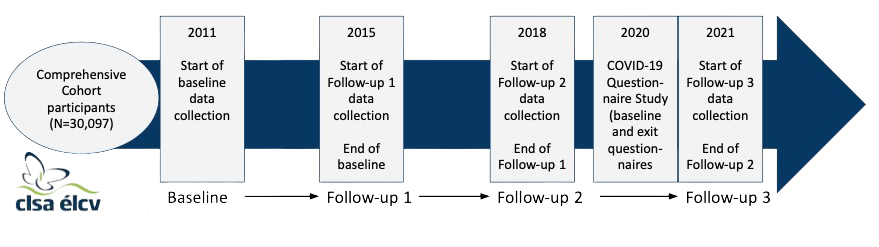

Many biomedical research studies in the past have collected biological material. What sets modern biobanks apart, however, is the scale on which these data are collected. Modern biobanks (e.g., Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging, UK Biobank, All of Us Research Program) typically recruit tens or hundreds of thousands of participants, regardless of their health and disease status, and prospectively collect or access many different types of data on health behaviours, health outcomes, and environment. Because these data are collected without any specific research questions in mind, they are very valuable to many different research questions. For example, we have used electronic health record-linked biobank data to understand how genetic factors for schizophrenia (PMID: 31416338) and loneliness (PMID: 31796895) affect medical conditions diagnosed across the life course.

What are longitudinal data?

Longitudinal data are a type of data collected by repeatedly observing or measuring the same people over a period of time. These data are especially valuable because they show the temporal ordering of events, such as how people respond to prevention and treatment strategies. Longitudinal data can also help us understand differences in how health changes over time, including why some people develop disease early in life, while others remain disease-free for decades. Longitudinal data are a core feature of biobanks.

Example of a project centered on biobank and longitudinal data in the Dennis Lab:

Depression that accompanies cognitive decline and dementia.

The prevalence of dementia in Canada is expected to triple by 2050 due to an aging population. Dementia leads to a decline in cognitive function, memory, thinking, decision-making skills, and changes in mood and behavior, with depression being more than twice as common in those with vs. without dementia. Current treatments like antidepressants and counseling are mostly ineffective, suggesting that depression in dementia might be a different disease than depression alone. Genetic factors likely contribute to this risk, but the specific genes and their mechanisms are unknown. We are studying the genes and molecular changes that underlie depression in cognitive decline and dementia using longitudinal data from multiple biobank datasets and population-based cohort studies. We hope that this research will help us develop new treatments. Throughout the project, we are working closely with dementia knowledge mobilization experts and persons with dementia to ensure the findings are meaningful and accessible.